Tap water (also known as municipal water, water from faucet, or running water) is commonly used for drinking, cooking, and bathing. It's generally provided for and regulated by a governmental agency for the purpose of keeping people - not bonsai trees - healthy and safe.

Fortunately, many tap water sources are also safe for bonsai trees and other potted plants; using tap water for your bonsai makes the most sense unless you know there is a problem.

Despite tasting like just water, tap water (and other water) typically contains many trace elements and compounds that contribute to its taste as well as the way that it interacts with people and plants. For plants, the trace amounts of elements like iron, manganese, sulfur, and calcium among others can be beneficial, providing nutrients that are not readily available in the soil or potting mix. It's when some of these minerals are present in higher concentrations that you may start to see problems with plant growth.

Symptoms of Water Quality Problems

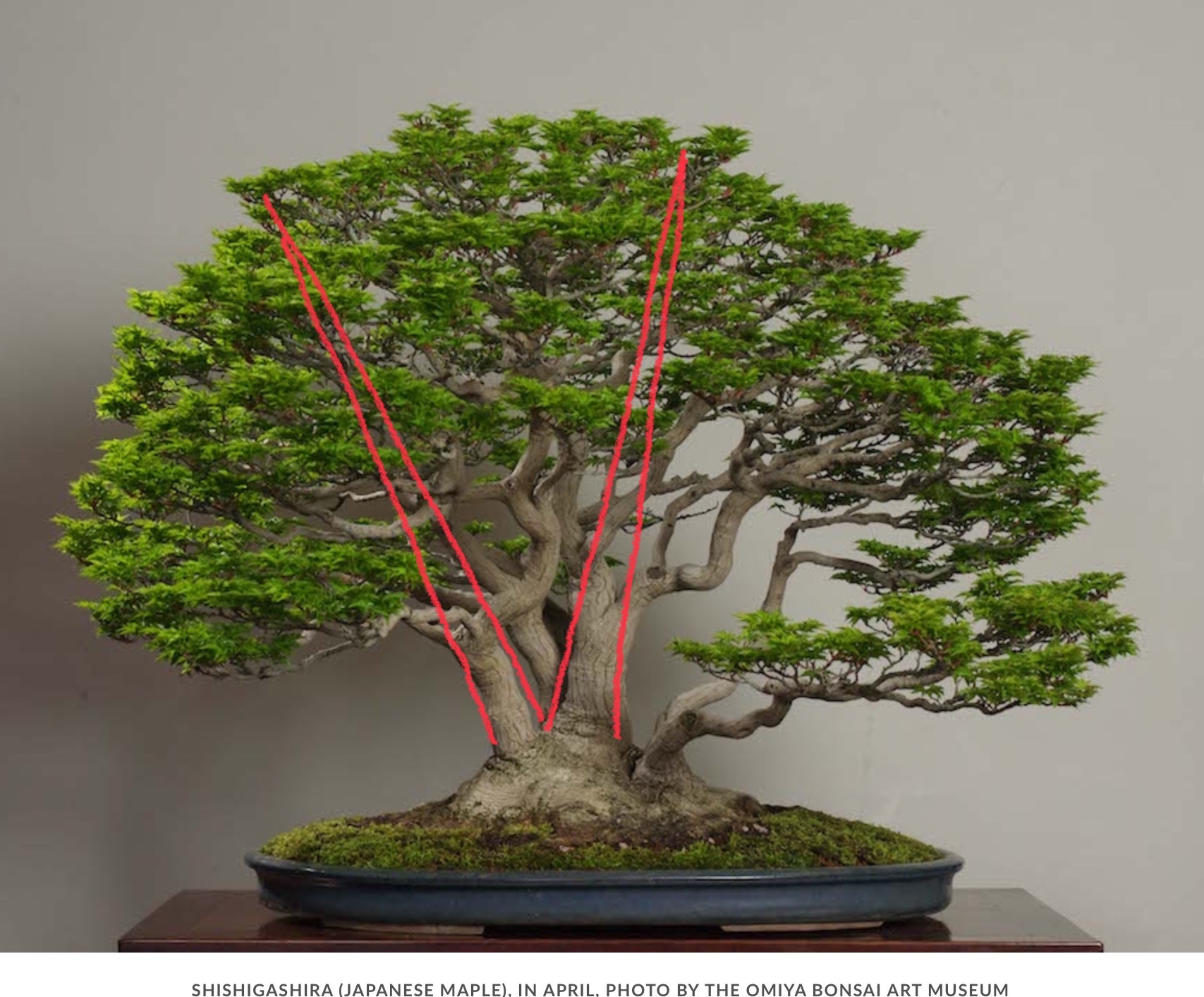

If you have a few bonsai plants of different species you will notice that some grow better than others under certain conditions. Some species are more sensitive to the mineral content of the water than others. Deciduous species tend to be more sensitive than conifers, with Maples being a common bonsai subject that is very sensitive to water chemistry.

These symptoms are among many others that may be indicative of water problems:

- Stunted new growth, or new growth that starts normally but then withers and dies.

- Margin burn on deciduous trees, particularly maples.

- Chlorosis, or other nutrient deficiency symptoms; the presence of excess minerals can interfere with the plant absorbing other minerals.

- General weakness and susceptibility to disease and insect attacks.

- Buildup of white residue on the base of trees, or on the rims and sides of pots.

How to Research a Suspected Water Quality Problem

If you think you may have a water quality issue, there are a few simple steps that you can take to identify what the problem may be:

1. Talk to other local bonsai and plant growers that share the same water source and ask if they are having problems with growing certain species. Ask if they have identified problems with the water in the past and what solutions they use to get around the problems.

2. Use a TDS Meter to test the level of minerals in your water. TDS stands for total dissolved solids. TDS meters give you a reading that combines many different elements, such as Sodium, Calcium, and Potassium, etc. A general rule of thumb is that a TDS reading from 0-150ppm is usually fine for plants; 150-250ppm is not perfect, but most plants will still do fine; and 251 or higher ppm is an indication that many plants may struggle to grow in containers. Don't be fooled that lawns and trees in the ground are growing fine - the mineral content of the water has much less impact on roots growing in the ground than those growing in containers.

3. The US Federal government requires that municipalities publish an annual water quality report. The reports show the average and maximum contaminant levels of various elements and chemicals that can make people sick. Hidden within these reports are typically the details you need to determine if your tap water will make your plants happy, or less-than-happy. Use a search engine to look for "[YourCityName] Water Quality Report". In many cases these are PDF documents that you can find on the web. The report for Walla Walla, Washington in 2019 shows a TDS of around 50 - a good sign for people trying to grow carrots. Meanwhile, if you live in Albuquerque, New Mexico, you might shudder at the TDS reading of 280 and Sodium content of 31ppm!

Toxicity Threshold for A few Important Elements

Some plants can grow in salt water, but for us bonsai lovers, salty water is generally a bad thing. Here are some thresholds to avoid for growing tree species common for bonsai:

- Calcium, also reported as "hardness" in some cases, is an element that plants do need a lot of, but in excess it causes problems with absorption of other key nutrients. If you see white residue on your plants around the base or on the leaves, you may have excess calcium, which is commonly referred to as "Hard Water". Calcium does not typically cause toxicity; it instead causes magnesium deficiency in some plants when it is present in excess.

- Sodium concentrations in your water should be 10-15ppm maximum. The toxicity threshold for many plants is at 25ppm or higher, but build-up of this same mineral that you use to season food can be bad news for your bonsai. If your water contains 25ppm or higher, you should mitigate the problem quickly.

- Boron is among the most problematic elements for plants - they need it in concentrations of 0.7-2.0ppm, below 0.7ppm many plants struggle to absorb the element for their metabolic needs, while above 2.0ppm Boron causes toxicity in many plants. If you have high Boron you'll need to lower it to get good plant growth.

About "Water Softeners"

In many locations in the southwest United States it is common to use a "Water Softener" in your home to treat water for hardness. The problem that people are avoiding is calcium spots on their dishes and glass shower doors. To do this, a water softener injects sodium into the water, which raises the overall salt content, but prevents the calcium from depositing onto surfaces.

Because sodium at high concentrations is deadly to most bonsai species, this can be the cause of many heartaches.

DO NOT WATER BONSAI with water that has been treated with a water softener! The sodium content will kill almost all bonsai species (although we happen to know that Dwarf jade, aka portulacaria afra, can survive it for quite a while!) Keep in mind that even outside irrigation water may be routed through a water softener depending on how it was installed in your house.

Treating Water to Mitigate Problems

While something like a Brita filter will lower the TDS of water, it is not a solution that will lead to robust plant growth. Brita filters are at example of systems that use activated carbon - which is basically charcoal - to absorb some minerals. However these filters remove some elements and compounds more than others, and since they are designed for people, they are not particularly useful for improving bad water for plants. "Whole House Filters" are like giant Brita's and do little more than improve the taste of water in most cases; and in the worst cast, they act like water softeners.

Reverse Osmosis ("RO") filtration is used throughout the world to create potable water from ocean water, and you can use it to purify water with high TDS readings for use with bonsai. Despite a relatively high up-front cost, RO is a good solution for bonsai growers in many cases. Systems are available for garden use that cost only $200 and will purify hundreds of gallons per day. The down side of most RO systems is that they use the municipal pressure to drive the purification, leaving you with a container full of water that you'll either have to move by hand or buy a pump to use.

Finding a different source of water is another solution; rainwater is the most commonly tapped solution. Rainwater is very low in TDS, and tends to be more acidic than tap water, both of which is good for plants. Combining rainwater with tap water can extend the rainwater while also avoiding nutrient deficiencies that using rainwater alone can cause.

If you have to treat your water, keep in mind that RO and rainwater and other solutions that remove nearly all the trace minerals from a water source require that you re-introduce a good mix of minerals. Use a baseline nutrient like Cal-Mag solutions or total nutrient solutions like Dyna-Gro.

We have a short video available, Water for Bonsai 101: Adjusting pH where we explain water chemistry and how it can impact your bonsai trees. Watch the video if you'd like to learn how you can adjust your water pH for optimal bonsai tree health.