I wanted to share my thoughts, having had been a bonsai hobbyist turned professional, practicing bonsai in LA through my experience of engaging with hundreds of people through workshops and private work as well as having worked on thousands of trees. This can apply to Southern California at broad, but may contain commonality towards the practice of bonsai as a whole. It is not my intention to paint all hobbyist of a region within a common brushstroke–rather to share my experience of locality based hurdles through observed experience.

Post Topic Index:

Climate Considerations

Disease Considerations

Chemical Product Recommendations

Water Quality

Addressing Water Quality

The Practice of Bonsai and “Maturing a tree”

Early Development

Intermediate Development

Advanced Development/Refinement

I will break this down into 2 categories of critique:

First through the horticulture of bonsai as it pertains to the local climate, water quality, hardiness of species, and how we can evaluate all of the prior. Second is application of bonsai as a craft and an art–what can we enable in our practice to increase our long term success and enjoyment of bonsai?

As how all bonsai work should be derived from, we always consider the health of the tree first. With many Japanese and domestic trained professionals, as well as abundant information from the internet, we are inundated with the latest techniques, aesthetics, and bonsai trends. I think people are very eager to apply and show off their knowledge of techniques, but it is important to remember a technique is only a tool and it is rather the application of the tool that is more important than it’s use. Just as a chef with superb knife skills, but a terrible palate makes awful tasting food the practice of bonsai without understanding of motivation, purpose, and principal results in inferior trees. The most fundamental of this principal is the health of trees!

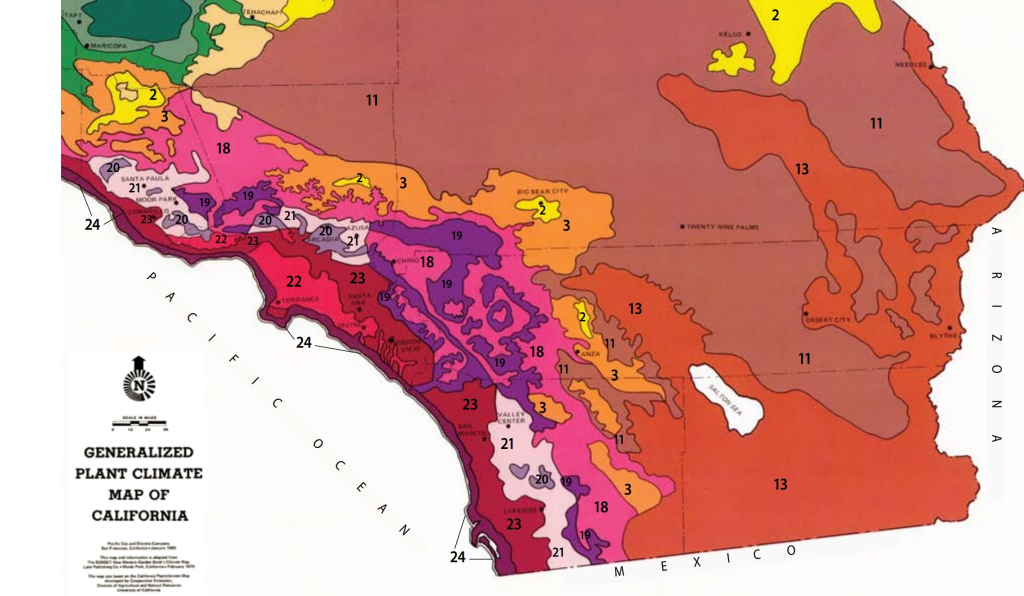

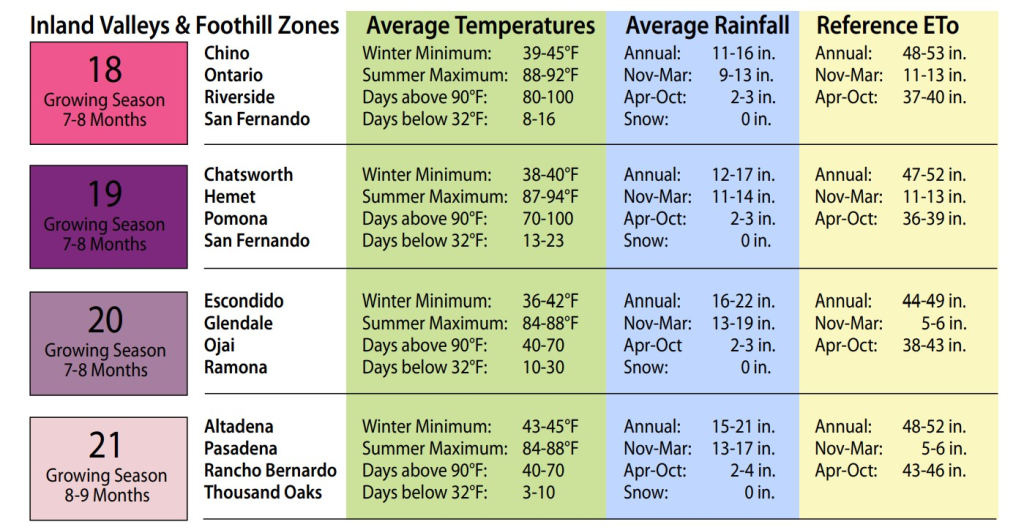

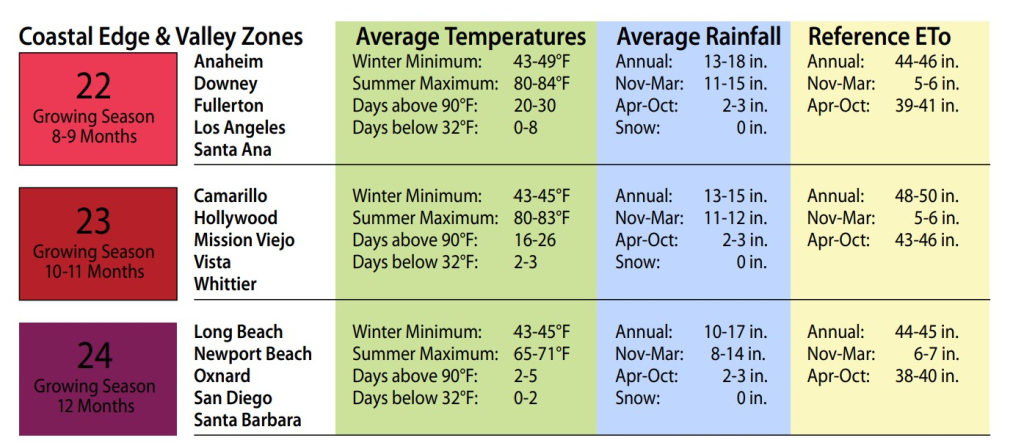

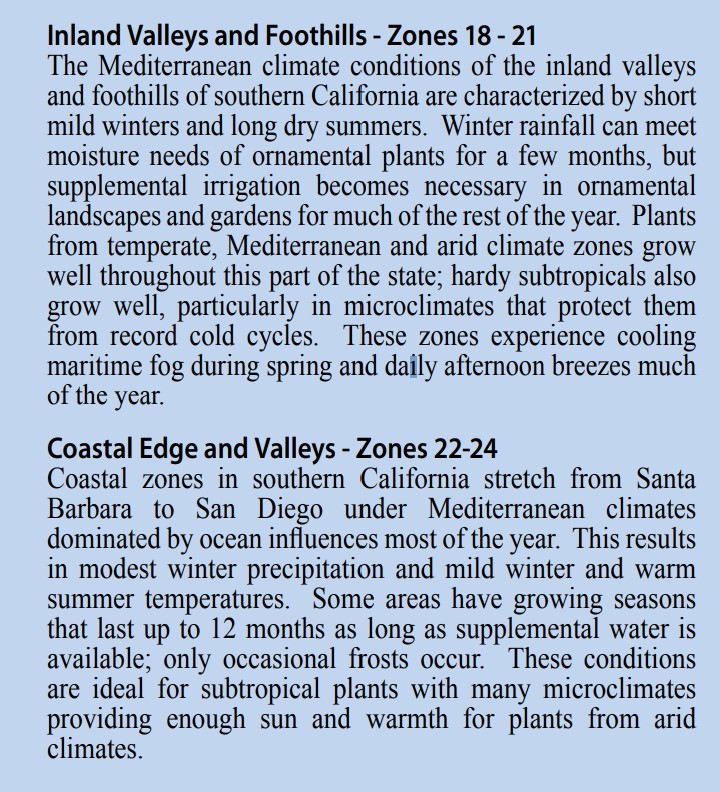

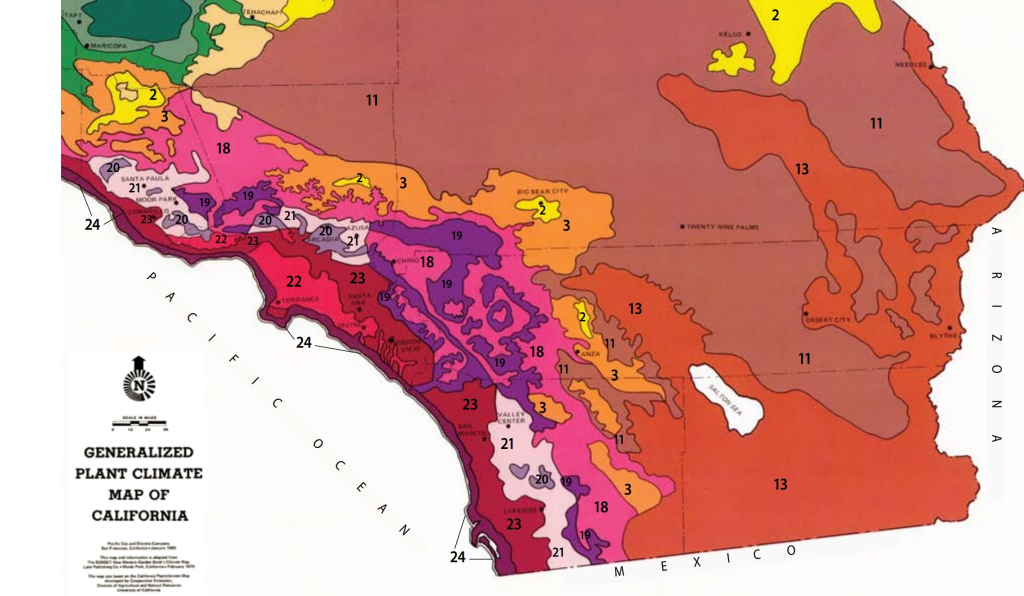

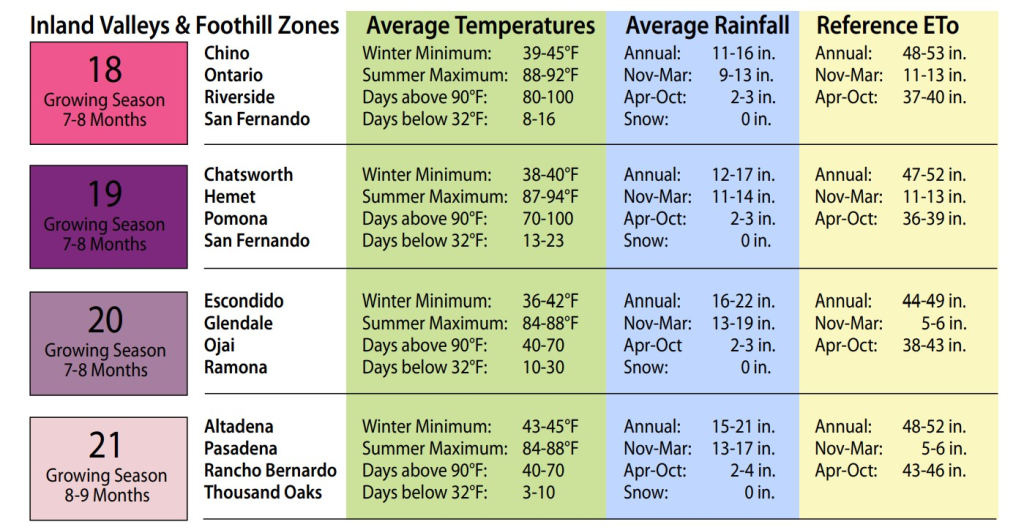

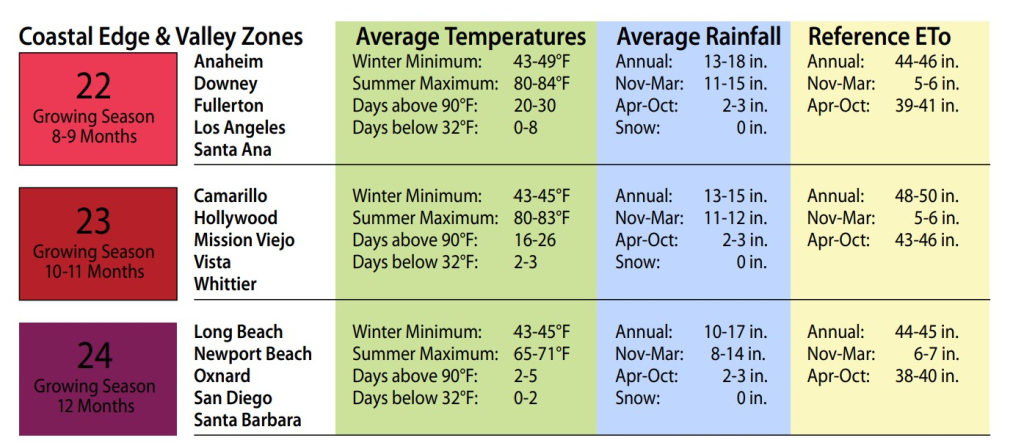

To start lets consider the climate of Southern California. We have quite a few microclimates (I will exclude the mountains and high desert which are the most deviant and have the smallest bonsai practitioner populace) which include coastal regions, low elevation hills, the valleys that lie in-between, and mountain foothills. In general Southern California is a mild, slightly temperate climate–deemed Mediterranean with low annual precipitation (mostly around winter) and arid weather. During the late spring to early summer months we experience significant marine layer as result of cool, moisture laden air coming off the ocean being trapped by hot air off the land. Your proximity to the coast then determines the amount of offshore humidity and subsequent reduction in temperature received. In general coastal climates will have greater overcast weather, higher humidity, and smaller range in temperature from the annual absolute low to high. Moving inland to low elevation foothills (500-1000 ft appx) such as the West LA hills or similarly low topography mountains, are less afflicted by deep marine layer with more sun, a wider temperature range but overall still mild. In between these 2 regions we have the valleys which are significantly hotter, with abundant sunshine and colder winter temperatures. Humidity is further decreased. Lastly we have the mountain foothills which exist on the fringe of the valleys against our large mountain ranges in the 800-2000 ft range. Climate in those regions are quite similar to the valleys but have lower winter temperatures.

The following pictures are from a free PDF provided by: https://landdesignpublishing.com/lpcg/

Climate Considerations:

Okay well that was a lot of information just on climate zones. How does this apply then to bonsai? Well we can first separate these by regions which are more or less temperate. The coastal regions and low elevation hills tend to be much more mild and winter temperatures seldom dropping below the high 40s. Trees that prefer some semblance of dormancy such as maples, prunus species, native mountain junipers, and others tend not to be as hearty. The valleys and mountain foothills are much colder in the winter, to the low 40s (occasionally high 30s). In general, short of tropical varieties most species benefit from some chill period and will grow heartier in the spring as a result. Even so temperatures are not truly cold enough for high mountain species like white and ponderosa pine.

Humidity levels also vary relative to your proximity to the coast which sometimes enable trees like black pines and high surface area junipers, like chinensis varieties (kishu, itoigawa) to grow faster, but some potential concerns with fungus. A big influence in growth characteristics and hardiness will be the amount of sun or our local marine layer which changes seasonally but generally is more dominant on the coast. Areas like the low elevation foothill or transition regions to the valleys tend to benefit from the humidity of the coast but are not burdened by marine layer and get great sun. These are great microclimates for many species, but tend to be mild overall in the absolute temperature range. More inland during intense summer heat shade cloth is absolutely necessary. But on the coast you might be able to get away not using it at all! This of course is relative to your sun exposure. Are you getting the full day of sun or windows cut off by buildings and surrounding land?

Disease Considerations:

There is another factor that relates to health I like to call disease pressure. Are you located in areas with minimal airflow or without daily breezes? Close proximity to industrial/dense residential areas? Cool humidity with not enough sunlight? It is important to note that there are pathogens everywhere, some harmful to plants and others not. There are introduced diseases from plant/food import and conversely, high elevation species or non native ornamental varieties may not have natural resilience to fungus/insects in our local areas. The best approach to deal with all these potential issues is just to grow your tree strong! Just as a strong immune system resists the abundant bacteria that surrounds us daily, a healthier tree will be more robust against disease. In short, a preventative approach is best! Although there are systemic fungicides and insecticides, in general application of these are more akin to treating symptoms as opposed to addressing the root cause. It’s like seeking dopamine hits for my depression instead of addressing the sources and working with my therapist, only that I don’t have a therapist.

BUT…inevitably it is impossible to grow trees in 100% perfection and health all the time, so here is a list of products I use and recommend. I just would advise that if your trees are constantly getting sick, maybe more chemicals is not the answer and you need to think about why its happening!

Chemical Product Recommendations:

Fungicides: Thiomyl based systemics (cleary’s 3336, bonide infuse-granular), mancozeb (great for blights, needle issues), immunox (powdery mildew, leaf spot), daconil (leaf curl/blights), zerotol (soil drenches, foliar spray), lime sulfur (dormant spray), copper (good general fungicide, but causes phytotoxicity and leaf deformation on soft/new deciduous growth)

Insecticides: Imidacloprid (systemic – bonide granular is the one I use), Malathion (aphids, leaf sucking bugs, also can use for root drenches), *Floramite (miticide – I strongly recommend a real dedicated miticide to deal with spider mites in Southern California)

*Often people are hesitant to buy dedicated miticides (this is NOT Bayer 3 in 1) because they are more pricey. Floramite for example is $120 for an 8 oz bottle, but the dilution rate is 1/4 tsp per gallon. For the average hobbyist that container of miticide will last you many years–if you have a lot of time and money invested in junipers it is a no brainer purchase instead of allowing your trees to get set back or destroyed by mites!

Water quality:

Water quality is a major issue in Southern California! Because we spend significant years in drought, water sources will shift between local ground water/reservoirs to “imported” or Colorado River water. If you’re lucky you get mountain run off/ground water which is the cleanest or in Carlsbad for example one of their sources is a desalination plant which is just a giant RO facility! But for the majority of socal residents, we have hard and akaline water! This makes deciduous trees such as Japanese maples notoriously hard to grow healthy in some areas with constant leaf deformation and fringe burning.

There are 3 general considerations to water quality. TDS, pH, and lastly mystery city ingredients.

TDS (Total Dissolved Salts):

This is the most impactful measure of water quality. TDS represents the all inclusive number of salts–not the stuff you put on your shitty mashed potatoes, but soluble ionic compounds, which may include calcium, magnesium, iron, manganese, etc

While our trees do need some degree of trace elements and “salts” in the water, a TDS value that is too high can have a negative effect. Looking back on our grade school science lessons, we learned about something called osmosis. Simply put, it is the diffusion of water across a semi-permeable membrane from a region of lower to higher concentration of solutes.

In theory if the water surrounding the roots have a high enough solute concentration, think sea water, the roots can actually desiccate and water will be removed. What this implies for high TDS city water however, is that the mobility or efficiency of the tree to uptake and move water is reduced. Additionally high TDS may contain salts/micronutrients in too great of an excess resulting in phytotoxicity.

Here are some TDS ranges:

Distilled Water: 0 ppm

RO Water: 5-30 ppm

Bottled Drinking Water: 15 ppm

Local Groundwater (natural source): 180-300 ppm

Imported Reservoir Water: 300-550 ppm (water that travels great distances have more dissolved minerals/salts in it)

Generally about 50-150 ppm is a good range to be in that contains enough dissolved salts to provide the tree micronutrients, but not so much in excess. Roughly 200 ppm is my observed max that Japanese maples still are okay in (not great). Over 300 ppm your deciduous trees will struggle and not grow as hearty.

pH:

A lot of people misunderstand pH what it means for the plant. We know that the acidic range of pH is 1-6.9 while the alkaline or basic range is 7.1-14. What pH is doing is determining the solubility of different micronutrients in the water and thus the plants ability to access it. A way to imagine this is pouring salt in a cup of water. After stirring it a lot it dissolves into the water and thus we say it is soluble. For discussion sake imagine that after stirring that cup that the salt your poured in still remained. That would be insoluble, in its precipitated crystal mashed potato additive form. Plants can access nutrients that are soluble, but not as mashed potato dressing.

This graph shows the different solubilities of common micronutrients across the full pH range. Thinner is less, thicker is more. Hint hint. Notice in the pH 8-9 range, commonly what city water is at there is a very high amount of soluble calcium and magnesium. Hmm makes sense with those white stains on our pots. Looking at iron the bar, it is very thin in this range. It is no mistake that when you buy soil acidifier products, they contain large amounts of iron! It is to make up for the deficit in these alkaline pH ranges.

A lot of literature, plant people, and professionals recommend a pH range around 6.5. Looking at the graph we can see that there is a little bit of everything available in that range. The sweet spot!

Mystery City Ingredients:

This is 100% anecdotal and speculation, so I don’t have clear quantifiable explanations here. But generally speaking, many counties will disinfect their water with algicides, bactericides, chlorine, and other chemicals that are deemed safe for humans in low enough ppm ranges but potentially can be phytotoxic or harmful for plants. This is not so measurable, but I believe it is another factor at play in water quality.

Addressing Water Quality:

So if we do not have access to good water quality, what are ways we can mitigate these issues? Solutions and trades offs listed below.

RO Water:

Pros – The brute force method of water filtration, will remove 95% of all salts in tap water. Filters can last years in bonsai use. Creates very pure water and clean slate to modify with micronutrients or fertilizers. When solute level of water is very low, not necessary to pH water either. Soil environment will dictate pH for clean, non salt buffered water.

Cons – Wastes water, RO systems use a back line to flush the filters. Initial cost can be expensive

Verdict – Recommended, but if you have a large number of trees the wasted water can be a concern

Dosatron Injection Systems or Siphon Systems:

Pros – Can introduce varying degrees of controlled injection of a fertilizer or acid into water line. Can correct for pH issues.

Cons – Does not address TDS, which is main pressing factor for water quality

Verdict – Recommended if your city water TDS is not too high and you just need to correct for pH. If RO is not practical or too expensive pH-ing your water to a slightly acidic range is still better than if you did nothing

Polyphosphate Water Softeners:

Pros – Cheap, polyphosphate beads form complexes with solutes in water that flush out without binding to surface. No hard water stains!

Cons – Changes water chemistry, not only binds to calcium and magnesium but other micronutrients as well. Tree may have growth deformities.

Verdict – Not recommended (I tested this for 1.5 years on my own trees). Maybe for a drip or soaker hose irrigation that you use when you are busy or traveling to prevent calcium clogging, but not good as a primary water treatment

Carbon Filters:

Pros – Cheap, removes chlorine, heavy metals, perhaps the mystery ninja turtle creating compounds in the water.

Cons – No effect on TDS or pH

Verdict – Recommended, but not as a primary treatment of poor water quality. Can be used in conjunction to previous methods.

Hardiness Tier List of Common Species for SoCal (recommended varieties)

Junipers: Very hardy, cold temperatures preferred but not necessary. Tolerates wider TDS range. Spider mites can be problematic. Native California junipers quite strong except on coastal regions. Procumbens, San Jose, and prostrata very strong also and acceptable in most micro climates. Chinensis varieties like kishu resists fungus more but can get heavy spider mites. Itoigawa resists spider mites but more susceptible to blight. Necessary to experiment to determine which one is better in your local area.

Oaks and Olives: Hardy, semi tolerant of high TDS . Likes heat and sun, not idea in coastal marine layer belt. Best in valley and transition zones.

Elms: Hearty, semi tolerant of high TDS. Will grow in most microclimates. (includes chinese elm, winged/texas elm)

Black Pines: Tolerant of high TDS and pH, but highly influenced by local microclimate. Low elevation foothill/transition region is best micro climate, valleys and coastal produce comparable growth, they like sun and heat. Can be fungus susceptible. Mycorrhizae does not develop in city water in socal, but can show up with RO. Clean water makes things easier but I have found through customers black pines thriving on otherwise very poor water. Tricky overall but if it does grow well in your area, it can be a very hearty choice.

Pomegranates: Hardy, semi tolerant of high TDS like oaks. Likes heat and sun, bad choice for coastal belt

Tropicals (Ficus, bougainvillea, etc): Not happy below high 40s, but tolerant of wide TDS range and will grow in most socal micro climates. Trees can get leggy and slow to develop in high marine layer climates however.

(I will add to this in the future and also include a list of trees which can be grown well with treated water)

Topic 2, The Practice of Bonsai

Now onto the second consideration, how do we practice bonsai as a craft turned art? I believe often that we are very much in an instant gratification society. This is not necessarily a bad thing, as the pursuit of efficacy, efficiency, and the production and subsequent packaging of information, technology, and food have often lead to great societal advances. It is easy to take for granted, as an end user consumer, the innumerous years of engineering, ingenuity, and hard work it takes to develop products and information we use everyday. I believe this also applies to bonsai. We see so many great photos of bonsai online and naturally, are inspired to make creations of our own. In absence of seeing great trees in person, as well as the ability to see or ask how it was made, we have nothing to go off of other than the apparent aesthetic–this is especially true for self practicing hobbyists. Bonsai however is an iterative and emergent art whereby application of the craft in stages, the final aesthetic is realized (this process can range from a few years to several decades). Taking a “front-end” approach or aesthetic motivated design practices bonsai as a pure art, such as a painting or sculpture that can be realized and maintained in “one iteration.”

My observation is that frequently trees that lack maturity, the necessary branching, the necessary health, are prematurely styled or forced into a finish aesthetic. We can wire, manipulate, and style branches to fit into a desired silhouette and aesthetic. This is fine if the tree could be maintained in perpetuity, however the reality is that all trees will continuously change and grow! A discuss this concept in my previous blog articles as well.

Maturing a bonsai + what stage is it at?

It is important to assess what stage your tree is at. Am I building the core features that may minimally change over the long term? Think trunk line, roots, and primary branching that can build the foundation of a design. Do I need to thicken the trunk? Create taper? Develop deadwood/lifelines (for junipers)? Thicken main branches (showing thick primary branch lines carry visual weight and can help convey age)? Do I need physically more compact growth? Smaller internodes? Earlier foliage origin point? It is important to invest time to develop these features that will result in a higher quality, more sustainable, and older looking tree. I call this maturing the tree. Would you drink the first decant of a freshly distilled hard liquor?! Maybe!!! But you also might go blind, destroy your liver…or die! Haha just kidding doing instant bonsai is not gonna kill ya. There is value in maturing a tree as opposed to rushing for a finished aesthetic. In bonsai there are not that many true shortcuts–they all entail some form of a trade off.

I have observed many practitioners so eager for the finished image, that the future is sacrificed as a result and the tree constantly cycles through stages of intermediate refinement and getting “restarted” every few years. Essentially a tree that no matter how many years you work on it, will never mature or improve. I say this not as a discouragement to bonsai, but rather that we should enjoy the process of creating trees and having nice bonsai will be a natural result.

Examples of early development

Growing trunk:

This may entail management of chops and thinning to direct growth, but more or less a tree is being grown strongly and less restricted.

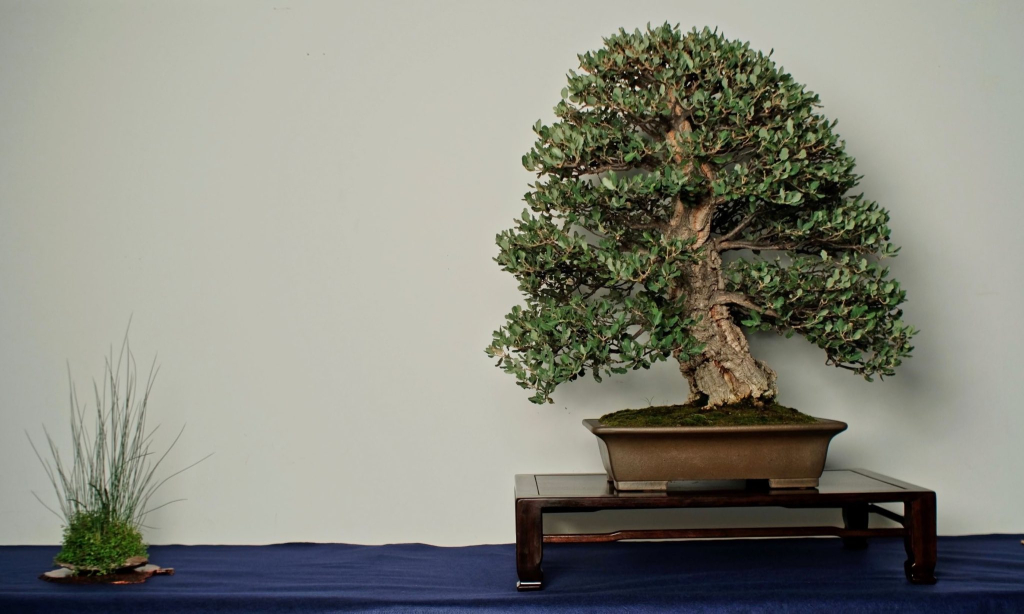

Cork Oak trunk, 2015 or 2016 pre apprenticeship

Developing roots:

Nebari can actually be continuously matured overtime, but the initial stages may involve developing the some degree of lateral root mass. Another consideration is the transition of trees from field grown/container situations to eventually bonsai pots, as well as the ability to get a tree in the smallest pot possible. Do you have a well ramified dense feeder root system immediate to your trunk? Is space being wasted by large tap roots? Building a compact and healthy root system means in the confined space of a bonsai pot, the tree has greater ability to thrive.

Trident maple nebari, circa Kouka-en 2018 apprenticeship

Developing branches:

Perhaps the most susceptible area for mistakes, branch development is influenced by species and can be tricky. For deciduous do the initial primary segments have sufficient thickness? Depends on the size of a tree but often a primary branch may need to grow for years before the first cut! Branch thickness for the primary line has some relevance in conifers as well as the degree of lignified mass also determines whether a branch flops in the absence of wire.

Cork Oak, potted version of this one year later is in my work portfolio. Still necessary to thicken some primary branches. Those branches I ended up growing close to 4 years before I finally decided to cut it from the first photo.

Examples of Intermediate Development:

Trunk lines, directionality, and/or taper should be established. We can start considering branch placement and design–also where is the origin point of foliage? Is necessarily compact or needlessly long? Perhaps through cut back, a good state of health, or structural wire we can produce foliage where desired. In general wiring of primary branch lines can involve a lot of creative bending (conifers) but once you get to the foliage bearing lines, the structure must be clean for sustainable design.

Secondary branch placement is being set, which is perhaps the future foliage pad bearing branch or in deciduous work we may be creating taper, cut derived movement in branches, and/or the starting bifurcations.

Branch building on trident maple:

Structural work, repotting, and setting up branches on redwood (work carried out over 6 months). Some regions left long to thicken.

Examples of Advanced Development or Refinement:

At this stage all the elements or building blocks of our design are present. Even major restylings are dependent upon available branching for cleanliness of the desired design. Deciduous may start focusing on density, the outer silhouette, as well as the softness or fineness of the branch tips. We can really start to showcase age at this step, rather then just a shell of foliage it is important to show off interesting branch lines (that we built in the previous steps) as well as fine branching that supports the foliage.

You must assess which stage of development your tree is at and the necessary work involved, or buy a tree which has adequate maturity from the point which you’d like to continue development.

Some black pine wire work, circa Kouka-en apprenticeship 2019

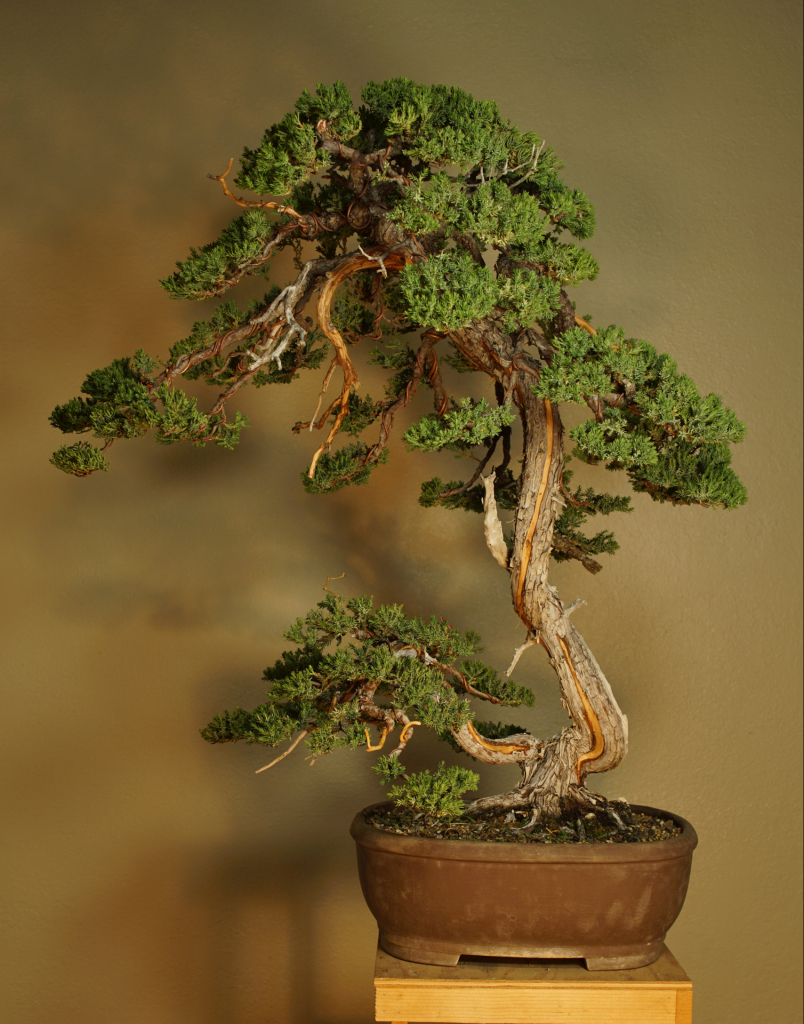

One of my favorite trees, a bunjin procumbens juniper styled post apprenticeship 2022:

Well that was another long one. I don’t write too often these days, but when I do it will always be a high quality substantial article. I hope this was of interest and provided some good food for thought. Blessed may you be in your bonsai journey.