Chinese Cork Bark Elm Progression, Part 1

The story of how I came to own this tree is rather funny, for me at least. Earlier this year at one of my workshops a customer brought several trees to work on, this being one of them. I was attracted to it and began to make some subtle hints to the owner that I would like to purchase it. Initially he was not keen but the following day I made him an offer he could not refuse and I became its caretaker.

The initial attraction

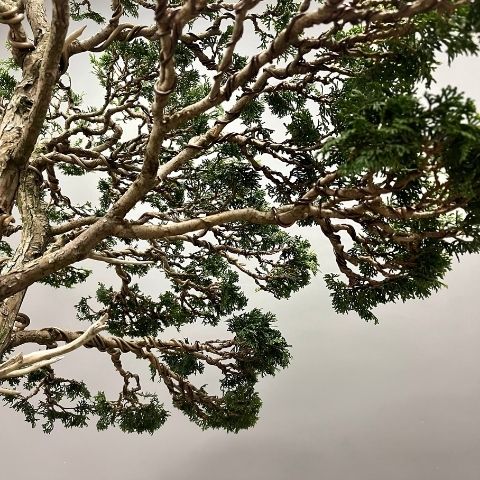

As is the case with most if not perhaps all of the locally available cork bark elms; they would originally have come from Stone Lantern, grown by Stephen Le Roux in the field. However most of the stock I've seen barring some exceptions, are single trunked specimens. I wanted something with which I could create a more natural deciduous form. I felt this tree had the potential I was looking for. It possessed many other qualities such as deeply fissured bark, scars of manageable size, nice trunk taper and movement and others.

The tree as purchased before any work began. Photo taken 15/08/2019

Repotting

The timing of this purchase was great as the tree was just beginning to bud and as I wanted to get it out of the sandy, composted mix and into a better draining growing medium I could still perform the repot this season.

Upon inspection of the roots I found them to be healthy although still a very immature root mass with mainly coarse roots and few fine roots, rather typical of mixes comprised of mainly fine particles that had compacted creating an environment not conducive to root development being largely devoid of oxygen.

The previous soil mix was very sandy with composted bark mixed into it. Such mixes are prone to compacting and not conducive to a healthy root system.

Elms can be propagated from root cuttings {Read more about the process here} which often have added character to them. Rather than simply cut the roots I did not want and discard these pieces I decided to pot them too. When cutting elm roots I find them to be very fibrous and unless your tools are very sharp it is easy to end up ripping fibres instead of cutting them cleanly, which may retard the healing process. I don't as routine seal cuts on roots, it hasn't seemed to be necessary in my experience.

Root cuttings can be a fun way to propagate elms with lots of character. Unfortunately none of these struck, although I have no idea why.

I'd chosen a Reiho container {Read more about Reiho here} with a simple bamboo relief detail, glazed in a baby blue. The colour would contrast well with the deep bottle green leaves of the elm and the shape would be a balance between the masculinity of the tree but the absence of hard geometric corners would complement the roundness of the future canopy.

The mix of akadama, pumice and leca which I used to repot the tree into.

My standard mix for developing deciduous trees is 2 parts small akadama and 1 part of pumice. The additional akadama would retain more moisture and store more nutrients, both of which will see this tree develop strongly. I also added a small amount of Leca although this was not entirely necessary.

After repotting, a thin layer of dried, grated sphagnum moss mixed with collected moss, treated in the same manner was applied. This surface finish acts as a mulch and keeps the surface soil particles from moving thus encouraging surface rooting. It also creates an ideal rooting medium for the collected moss to grow, which it does in a matter of weeks. This method of encouraging moss growth is preferable over placing pieces of moss around your trees, as this method usually results in the moss curling up in the heat of summer. Plus by mixing various collected moss species one can create a very natural looking surface around the base of the tree.

After repotting, a mix of sphagnum moss and collected green mosses is applied in a thin layer.

Design and Initial Work

As mentioned already, my goal with this tree is to create a more naturalistic shape. However much of the existing framework which existed was either horizontal or just above. This would need to be changed, altering the angle to be more vertical.

Very horizontal branches would need to be changed.

Fortunately there were no major scars facing the viewer when the tree is viewed from the front. However there were a number of smaller and less obvious scars, remnants from when it was being field grown. These would need to be carved a bit more and then sealed to promote callusing. As these were all fairly large cuts I used a putty type sealer, but for smaller cuts I used a liquid sealer. {Read more about treatment of scars here}

The tree with rebar in place and the branch angles changed.

Aluminium wire alone would not suffice to bend the fairly developed branches so I would need to cut a wedge and using some rebar as an anchor, bend the branches upward. It was necessary to secure the rebar into position and I used the trunk as the anchor, also inserting the rebar somewhat into the container. Rubber from an old tyre tube was used to protect the trunk from damage. However I also needed to secure the bottom of the rebar to a screw which I had fastened to the base of the trunk, as the rebar immediately began to pull away from the trunk when I created tension at the opposite end.

3 Months Later

After a few months of allowing the tree to grow freely, growth being encouraged by fertilizing and good watering, it is time to thin the tree of unwanted branches to focus the trees' energy into those which remain and which I want to develop further.

Development of the tree over the past few months. Photo taken 05/11/2019

Wire Bite

Wire bite like this is not too much of a problem on this species at this point in the tree's development.

The wire applied in early spring, in the initial styling, is now clearly biting in. Wire bite is to be avoided at all costs on very thin barked trees such as Japanese maples, Azaleas and even Olives. The evidence of wire bite on such species can take a very long time to disappear, however when building a tree they are to some extent non-consequential as the branches would still undergo much thickening - however traces of the wire bite may still remain.

Pruning

One needs to envisage the overall final design of the tree to a great extent and through pruning and wiring work towards that end goal.

Pruning unwanted branches using a branch cutter.

Some of the thoughts going through my head (having already determined the basic look of the tree) when I was pruning this tree were:

- What will this branch look like once its has developed some girth?

- How much do I need to exaggerate the curves wired into the branches that they will still be visible once they have thickened?

- What will the negative space look like between the branches?

- Where is the negative space too big and with which branches can I fill it adding to the positive space?

- How do I deal with ramification; ensuring good taper from trunk through to branch tips?

- Will I have sufficient "ports" through which sap can flow to feed the fine twigs at the future outline of the tree to avoid dieback?

- What internodal distances do I retain at primary branch level, as this will become progressively less the closer I get to the outline of the tree?

- With future pruning, will I be able to hide or heal over the scars?

When working with deciduous trees one needs to have long term commitment to the process. Initially progress is at a snail's pace as you grow out only to cut back. However each time this is done the ramification of the tree exponentially increases. Suddenly, after a few years of patiently working on the tree you will be able to stand back and appreciate the effort you have gone to and your patience will be rewarded.

Wiring

After pruning away the branches determined unnecessary, according to the thinking process above, I again applied aluminium wire, trying to wire either opposite to the direction used earlier in the season, or to avoid laying wire into the grooves created by the wire bite.

Wire is now used to better position the growth which developed since spring, with a generally vertical orientation. Care was taken to give the first section of the branch some movement.

Bear in mind that clip and grow method of styling will also be employed in creating this tree so the focus now is ONLY on the first few cm's of each branch. Once they have developed the required girth the branch will be cut back and the process of growing out and cutting back will be repeated.

Unwanted Moss

Killing unwanted moss with undiluted vinegar.

One of the worst tasks you can neglect to do with any cork bark variety of plant or even pines for that matter, is to allow moss to develop up the trunk. This constant moisture on the bark causes it to rot leaving behind a smooth trunk. In some cases the only recourse is to layer the tree above this section. So it is best avoided. In this case I sprayed undiluted vinegar, using the nifty pressure sprayer attachment attached to a used water bottle, on the moss which almost instantly kills it. After it has had time to thoroughly dry I will brush it off with a nylon or pigs hair brush.

Final Notes

After pruning, all cuts were once again treated with the appropriate sealer. If there were any areas damaged when wire was removed, these were also sealed.

Sealing smaller cuts with Top Jin Paste

The tree was placed back on the bench, to be allowed to grow freely till the end of the growing season when it will be assessed again.

After completion of the work described above.